The Source of Art and Sciene Is the Power of Reflection

Abstract

Examining scientific creativity through the lens of artistic exercise may permit identification of a path towards an institutional environment that explicitly values and promotes transformative inventiveness in science. It is our perception as an artist and natural scientist that even though creativity is valued in the sciences, it is non institutionally promoted to the same extent it is in the arts. Acknowledging creativity equally acts of transformation and central to scientific pursuit, actively utilizing chance and failure in scientific experimentation, are critical for step changes in scientific knowledge. Iterative and open-concluded processes should be modeled after insights from a range of practices in the visual, performing and media arts. Successful institutional implementation requires training through a long-term process of unlearning and learning, organizing interactions to critique results, designing experiments to comprise trial and error, and edifice common and private spaces that promote gamble encounters across disciplines and with not-academic sectors. As a natural scientist and an artist, we phone call for bringing such a transformative creative arroyo into scientific practice as a guiding principle for organizational and cultural development of the university.

Introduction

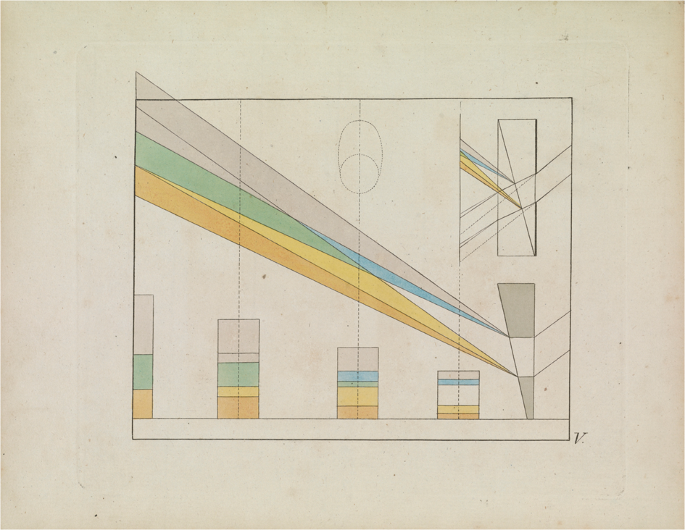

Comparing the arts and sciences, non everyone may think of natural scientific discipline as a artistic endeavor in comparison to artistic practice. For the longest time, science was rather associated with discovery of what is already at that place than bodily creation (Barasch, 1985). It is telling that the discussion 'creativity' only appeared about 1 hundred years ago (Whitehead, 1978) and for the most function stayed in the realm of artistic production, despite the shut relationship of art and science noted by many gimmicky scientists (Root-Bernstein et al., 2008). Even Goethe considered his scientific theory of colors (Fig. ane) his greatest achievement, not his poetry, illustrating how close creative and scientific pursuit may align. Yet in natural science, you are taught the answer, in arts, the questions, process and material production. From our point of view as an artist and a natural scientist, we strongly contend that close observation of artistic creativity (Collingwood, 1937), divers equally ideas and actions that transform laws, principals, materials, and thoughts both of the artist and the audiences, can be informative for scientific progress. Of import lessons about educating for and promoting creativity in the sciences can, in our experience, be learned from studying the creative process in the arts. The post-obit comments collate our thoughts from an artistic and natural science indicate of view.

Goethe's theory of colour and diffraction of light. Even though J.W. von Goethe is known today mainly as a literary author, he conducted basic science throughout his life and considered himself as much a scientist as a novelist and poet (reproduced from von Goethe (1810); paradigm in public domain)

Framing the issue

Both arts and sciences rely on a foundation of mastering methods and conceptual tools that require familiarity with the norm in lodge to question it. As much as a visual artist has to encompass and engage the histories of visual, cultural, conceptual and social questions of the past and present, and deal with central laws and skills governing the formulation, production and reception of visual art, the scientist must accept a basis in, for example, statistical methods, chemical reactions or ecological theory. Both artist and scientist must so synthesize their aptitude beyond simply fine art or science, beyond following rules and relying on faux to become creative. Key is often a conceptual accelerate rather than a sole focus on the physical product itself. This can be thought of equally the "transformative moment". Fifty-fifty appropriation and placing known objects into new contexts can develop original thoughts, exemplified by Sturtevant'south copies, Duchamp'due south ready-mades, or the Mail World War Two explorations in spontaneous musical compositions in BeBop based on standard tunes raised by Charles Parker. But but copying what has been washed earlier, without arriving at new insights, is neither creative nor transformative. One may argue it does not even constitute practicing fine art or science at all.

Relying on cognitive skills, conceptual tools, the noesis of precedents and processes, forth with the merger of intention and intuition guide 'what-if' questions, and are important avails in the toolbox of transformative artistic creativity. Common in art but rarely practiced in the natural sciences—and a critical aspect for a creative spark—is the ability to make associations between or blend (Turner, 2014) disparate parts of cognition and experimental evidence. This is called the fine art of intelligent perception (Bohm, 1976). We agree that the caste or probability of creativity in science relies to a certain degree on personal aptitude (Feist, 1998), besides as acquired cognition and skills with important insights for teaching creative inquiry (Mumford et al., 2010; Scheffer et al., 2017) and developing creative potential during a career (Mumford et al., 2005). In addition, every bit we argue below, the probability of creativity in natural science is a directly function of a broad range of situational attributes that tin be manipulated. These situational attributes are in our opinion non sufficiently considered by natural scientists and scientific discipline administration for promotion of creativity. Similarly, the explicit nurture of inventiveness is all-too-oftentimes absent in scientific pursuit and its education fifty-fifty after a long history of studies examining scientific practice including aspects of creativity (De Bono, 1973; Latour and Woolgar, 1979). We exercise not intend nor are nosotros qualified to advance the scholarship on creativity from a psychological or philosophical bespeak of view or provide an in-depth overview of the associated literature (e.g., DeHaan, 2011; Lehrer, 2012; Turner, 2014). Rather, past insisting on an important responsibleness of scientific institutions to provide the organizational foundation for private inventiveness, we intend to move this discussion on the framework of artistic creativity to the middle of the academic discourse also for the natural sciences.

Entry points for organizational back up of creativity

Here we hash out lessons for scientific creativity that may be gleaned from an observation of artistic creativity through an organizational lens. Fifty-fifty though inventiveness can in many cases exist an individual pursuit, it is also relevant to groups and networks, and includes audiences and stakeholders. Near mechanisms that promote scientific creativity possess both individual and organizational dimensions to varying extents and we consider these jointly for the purpose of our discussion. From our art and natural scientific discipline perspective, we propose to prioritize the following half-dozen entry points for promoting scientific creativity: acknowledging creativity equally an essential nugget; recognizing chance in identifying new directions; constantly critiquing one's own research, as well as each other'due south; trial and fault to accelerate discovery; allowing mental space to reflect on scientific results or plans; and value creativity to a greater extent in your own work, in the work of your advisees and your institution. These entry points for the natural sciences are discussed below and compared to the arts.

- 1.

Inventiveness—that is, developing original ideas and concepts—is the basis of creative exercise. But as with art, natural science requires creativity and individuals, as well equally institutions must acknowledge the pivotal importance of creativity as a defining feature of scientific advancement. It is not, as Kant (1790) put it, a matter of learning and copying methods to arrive at a scientific accelerate alone. As with art, and then does science require creativity. Natural scientists must approach their enquiry with the same rigor and expectation for novelty as artists do, which in our experience is not sufficiently the case despite longstanding investigations into scientific innovation in general (Knorr-Cetina, 1981). Recognizing that natural scientific discipline requires creativity, we can capeesh that creative practice may even provide a template for inventiveness not only for scientific exercise by faculty (Hoffmann, 2012) but besides by technical staff in many natural science disciplines (Wylie, 2015). Nosotros therefore propose that an artist'south viewpoint may provide researchers and research organizations with a template to advance creativity in the natural sciences. Making creativity a primary mensurate of success by because it a significant evaluative metric concurrent to publication records and other assessments would add together structural support for creativity in scientific discipline. The natural sciences could then besides be called a creative profession.

- 2.

Chance has often been quoted every bit an important factor in promoting creativity. The apparent chance "discovery" of photography by the artist Louis Daguerre resulted from accidental spillage of mercury in a cabinet storing argent-plated copper plates revealed the latent image on a plate. Similarly in science, Wilhelm Röntgen discovered ten-rays in 1895 when a chemically treated screen placed in the laboratory started to glow by exposure to a shielded cathode lamp; and Alexander Fleming observed in 1928 that staphylococcus was inhibited when a petri dish was accidentally left on the laboratory bench, leading to the development of modern antibiotics. Allowing for chance to occur in natural science, or even promoting and recognizing valuable take a chance results, is anything but piddling. Most scientific experiments are designed and taught to reduce adventure to allow just certain questions to be answered, meaning that today's scientist is often ill prepared to utilize unexpected results. On recognizing chance, Louis Pasteur famously remarked during a lecture at the Academy of Lille in 1854 that "in the fields of observation, chance favors only the prepared mind". A scientific study as well often develops along the script outlined in a proposal, rather than irresolute management—as in many artistic processes—when the 2nd footstep is fully dependent on how the first step turned out. Funding in the sciences and reporting should be congenital on promoting chance rather than measuring success strictly past compliance with a plan. Scientific proposals may lead to more important science, if the transformative possibilities of a question were valued to a greater extent than simply meeting the presumed or already-demonstrated feasibility of the experiment.

- iii.

In art, cocky-critique and critiquing by peers often occurs during the entire artistic process. Each castor stroke is evaluated, each move in a dance routine scrutinized as role of the process of cosmos—significant work can be improved in the moment. In the sciences, success or failure of an experiment is all besides oft evaluated only after weeks, months or fifty-fifty years of piece of work, when information technology is too late to change management or echo the study in a unlike way. Critiquing in the sciences typically comes at the end of a long process, and ofttimes in the form of brief comments that either lead to the acceptance or rejection of a publication or proposal. A more than artistic approach in scientific discipline would include having a continuous opportunity for feedback congenital into the scientific process, to allow for course correction in the inquiry that could result in a different experimental design or even changing the question.

- 4.

A heuristic approach in art allows many iterations to go the line in an artist's drawing simply correct. Egon Schiele purportedly drew like a bedlamite and threw nearly drawings in the fireplace if he did not like them. Today we estimate his creativity from the superb works that have survived which are the result of many iterations of trial and mistake. In comparison, scientific experiments are normally expected to requite an answer at commencement effort with no fourth dimension to perform another 1, making trial and fault a long-term process in the sciences. Error is therefore not seen as a practical intermediate step sufficient for reaching immediate scientific insights or essential for reaching a creative goal. Creativity could be promoted by starting with shorter and more than varied experiments where the vast bulk are expected to 'neglect', but lay groundwork for selecting the almost promising adjacent step. Concrete modifications in how natural science is organizationally supported and practiced may include: consideration of the time and space allocated to trial and error; expectation by graduate, tenure or hiring committees to demonstrate failure, also as to reward iterative research rather than unidirectional experimentation; and high-risk project funding for outcomes that are not already prescribed but the effect of open-ended exploration for at to the lowest degree role of the study to permit unrestricted inventiveness.

- 5.

The subconscious or "inspiration", the proverbial kiss past the artist's muse, is described every bit the mainstay of artistic creativity. In science, this may translate into the scientific reflection necessary to examine data, sketch out a proposal or plan an experiment. Mental or 'empty' (Scheffer et al., 2017) space where scientific creativity is strongest is not all that different from a focused state of mind containing irrational elements or intuition (Popper, 1935). Mental infinite to reflect on scientific results or plans is typically not given whatever priority in the sciences simply scientific progress is assumed to be a mechanic outcome of planned daily activities. Providing that mental space requires organizational and individual effort. Private preparation may include establishing cues for switching off and then on again, taking breaks, assuasive time to develop an idea and formulate responses in meetings, utilizing open up-ended discussion opportunities, and avoiding distraction. Many of these techniques are commonly encouraged in creative visual art, design, music and performance industries, yet have not been focused on natural scientists. Organizationally, the restructuring of infrastructure could provide space for artistic exchange and offer opportunities for structured critiques; create common areas to allow for spontaneous conversation and promote shared space betwixt colleagues who work on diverse issues, in an effort to promote word.

- 6.

Within the arts, creativity—as nosotros ascertain it here—is valued and supported as critical to both the process and outcome of artistic product. In the natural sciences, creativity is non explicitly valued by scientific institutions and therefore not perceived as desirable by the scientist. Often, questioning the norm necessary to create new processes and products is seen every bit being detrimental to an institution, requiring take a chance-taking and courage (Scheffer et al., 2017; Segarra et al., 2018). The number of publications, their citations, and the prestige of a periodical typically remain more important than the transformative procedure and outcome of the scientific product. Ideally all these metrics—too as the ensuing uptake by industry or impact on order—should be a reflection of creativity, but it is not assessed or valued in and of itself. The scientific advantage construction does non address this lack of recognition head-on. A modify in attitude by the scientist volition only exist achieved through an incentive structure and value organisation that encourages transformative creativity above everything else. The extent to which a scientist makes associations beyond disparate areas of study, and the blending or merging of ideas, may serve every bit a starting point for developing metrics of creativity, perchance through the diversity of institutional affiliations of authors. The diversity of methods and experiments used to create new knowledge may also manifest itself in longer scientific articles that develop a story rather than snapshot solutions.

It may turn out that inventiveness defies easy quantification in the natural sciences, as ideological, corporate and political circumstances challenge the unambiguous cess of creativity of the scientific product. Valuing and incentivizing creativity in the natural sciences may hateful supporting the mechanisms that we do recognize to enhance creativity, rather than by concentrating on learning inventiveness itself (Bohm, 1968).

Blending ideas may still require the solitude of traditional reading of the scientific literature, but unregulated interactions with colleagues and ensuing chance encounters may provide greater opportunities to foster a creative spark than meticulously planned research, for every bit much knowledge equally the scientist may possess. Valuing creativity will certainly include many priorities that some institutions accept already set for themselves, such as assuasive increased physical proximity between disciplines that are targeted for collaboration. Yet cardinal is to organize the incentive and support structure through the lens of how to promote creativity. When designing institutional structures, one may want to recognize that creativity is likely not the outcome of a universally applicable method that tin be enforced just a highly individual path to be explored. From our own experience as artist and natural scientist, infusing lessons from artistic creativity into this planning process volition enrich the effect.

Promoting creativity in the natural sciences with artistic practice in mind

Many proposals accept been fabricated over the by decades virtually how to advance inventiveness for industrial and professional innovation that include institutional and individual methods (De Bono, 1973; Couger, 1996; Hemlin et al., 2004). Hither we utilise the above-mentioned entry points that have emerged from an observation of artistic exercise and briefly highlight iii key organizational strategies that may promote individual and collective creativity in the natural sciences. The following strategies merely serve as an analogy of starting points from our indicate of view and of what is in some cases already expert, and will require more space than is bachelor here.

- one.

Railroad train respectful critique; a "working memory" (Baddeley, 1992) to recognize chance discoveries; reaching a mental infinite of heightened perception; and a state of mind that is accustomed or even expected of the artist, when in fact, the creative scientist is literally dreaming upward new realities. Such training is a long-term educational process, of unlearning and learning, not a brusque-term pedagogy, and may involve starting from either observation or theory. Art practice, intent and question may and so ignite new dimensions of thinking in the sciences (Bohm, 1969) and open up up avenues for art-scientific discipline education (Gurnon et al., 2013) besides every bit part of integrated science-technology-technology-arts-mathematics (STEAM) programs (Bequette and Bequette, 2012; Segarra et al., 2018).

- ii.

Organize regular interactions between scientists to critique processes and results; and experiments to contain trial and error. An institutionalization of future-orientation every bit explored at the Center for Scientific discipline and the Imagination of Arizona State University (Selin, 2015) builds on broad institutional support and individual engagement. These approaches likewise require an environment of trust to share insights and an environment of respect for creativity. A Co-Lab connecting artists and scientists may exam assumptions nearly critique in unexpected ways, and may promote needed chance-taking (Segarra et al., 2018). The arts may be specially effective partners for deep collaboration by providing "trading zones" that are divorced from disciplinary constraints (Brown and Tepper, 2012).

- 3.

Build common and individual spaces that promote chance encounters beyond disciplines and with not-academic sectors, and that allow for the mental space to generate the creative spark. Few of these suggestions are new in their respective fields, but little is practical in academic education (DeHaan, 2011) or practice in the natural sciences.

Finally, to leverage insight from artistic artistic practice it will be necessary to depart from considering natural scientific discipline as the antithesis of art, and to recognize that art and science share many basic requirements and techniques that promote creativity. We urge academic institutions and private scientists to take on this fence with the sincerity that information technology requires.

References

-

Baddeley A (1992) Working memory. Science 255:556–559

-

Bequette JW, Bequette MB (2012) A identify for art and design education in the STEM conversation. Fine art Educ 65(two):40–47

-

Barasch 1000 (1985) Theories of art. New York Academy Printing, New York

-

Bohm D (1969) On the relationships between science and fine art. In: Colina A (ed.) Information: directions in art, theory and aesthetics, an anthology. Faber and Faber, Great britain, p 33–49

-

Bohm D (1968) On creativity. Leonardo 1:137–149

-

Bohm D (1976) The range of imagination. In: Sugerman South (ed.) Evolution of consciousness, studies in polarity. Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, p 51–68

-

Brown AS, Tepper SJ (2012) Placing the arts at the eye of the creative campus. Association of Performing Arts Presenters, Washington, DC

-

Collingwood RG (1937) The principles of art. Oxford University Printing, London

-

Couger D (1996) Inventiveness and innovation in information systems organizations. Boyd & Fraser, Danvers

-

De Bono E (1973) Lateral thinking: creativity pace by step. Harper, New York

-

DeHaan RL (2011) Education creative science thinking. Science 334:1499–1500

-

Feist GJ (1998) A meta-analysis of personality in scientific and artistic creativity. Personal Soc Psychol Rev two:290–309

-

von Goethe JW (1810) Zur Farbenlehre. Cotta, Tübingen, Germany

-

Gurnon D, Voss-Andreae J, Stanley J (2013) Integrating art and science in undergraduate teaching. PLOS Biol 11:e1001491

-

Hemlin S, Allwood CM, Martin BR (2004) Creative knowledge environments. Creat Res J 20:1996–1210

-

Hoffmann R (2012) Reflections on art in science. In: Talasek JD, Quinn A (eds) Convergence: the art collection of the national academy of sciences. National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC, p 85–87

-

Kant I (1790) Kritik der Urteilskraft. Lagarde and Friederich, Berlin and Libau, Germany

-

Knorr-Cetina KD (1981) The manufacture of cognition. Pergamon Press, Oxford

-

Latour B, Woolgar S (1979) Laboratory life: the construction of scientific facts. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills

-

Lehrer J (2012) Imagine how creativity works. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston

-

Mumford Doc, Connelly MS, Scott G, Espejo J, Sohl LM, Hunter ST, Bedell KE (2005) Career experiences and scientific performance: A report of social, physical, life, and wellness sciences. Creat Res J 17:105–129

-

Mumford MD, Antes AL, Caughron JJ, Connelly Southward, Beeler C (2010) Cross-field differences in creative problem-solving skills: a comparing of health, biological, and social sciences. Creat Res J 22:14–26

-

Popper K (1935) Logik der Forschung: Zur Erkenntnistheorie der modernen Naturwissenschaft. Springer, Berlin, Germany

-

Root-Bernstein R, Allen 50, Embankment Fifty, Bhadula R, Fast J, Hosey C et al. (2008) Arts foster scientific success: avocations of Nobel, National Academy, Royal Guild, and Sigma Xi Members. J Psychol Sci Technol 1:51–63

-

Scheffer Grand, Baas M, Bjordam T (2017) Pedagogy originality? Common habits behind creative product in scientific discipline and arts. Ecol Soc 22(2):29

-

Segarra VA, Natalizio B, Falkenberg CV, Pulford Due south, Holmes RM (2018) STEAM: using the arts to train well-rounded and creative scientists. J Microbiol Biol Educ xix(1):19.ane.53

-

Selin C (2015) Merging art and design in foresight: making sense of emerge. Futures lxx:24–35

-

Turner M (2014) The origin of ideas. Oxford University Press, London

-

Whitehead AN (1978) Process and reality: an essay on cosmology. Gifford Lectures delivered in the Academy of Edinburgh during the Session 1927–28. The Free Printing, New York

-

Wylie CD (2015) 'The artist'southward piece is already in the rock': constructing creativity in paleontology laboratories. Soc Stud Sci 45:31–55

Writer information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional data

Publisher'due south note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This commodity is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits utilise, sharing, accommodation, distribution and reproduction in whatsoever medium or format, as long as you lot give appropriate credit to the original writer(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article'south Creative Eatables license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the textile. If material is not included in the article'southward Creative Eatables license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted apply, you will demand to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a re-create of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Lehmann, J., Gaskins, B. Learning scientific creativity from the arts. Palgrave Commun 5, 96 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0308-8

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0308-eight

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-019-0308-8

0 Response to "The Source of Art and Sciene Is the Power of Reflection"

Postar um comentário